Rigging resources

Information about the

sizes and types of rigging used in large square rigged sailing ships

British Navy and

merchant ship rigging information

A General View of the most

Approved Ship of Each Class in the British Navy with the exact dimensions of

her Masts, Yards, Rigging, Blocks, Guns, Gun-Carriages, Anchoes and Cables

according to the establishment of 1778. Printed for David Steel – 1781

This

publication, originally published as a 34” 23” sheet, shown in the following

figure:

Steel’s original sheet (from here) Excel version here

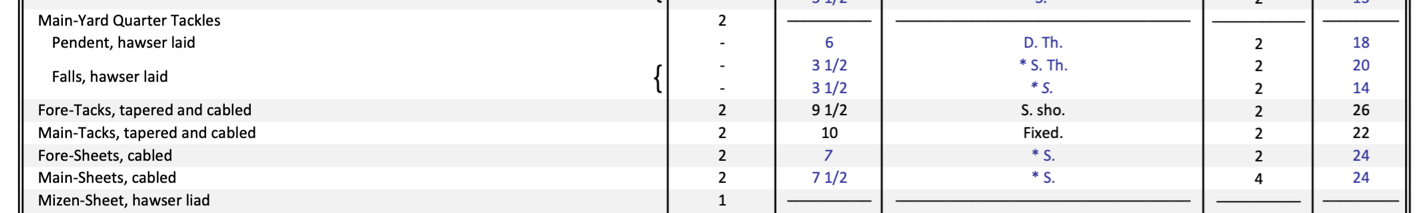

The

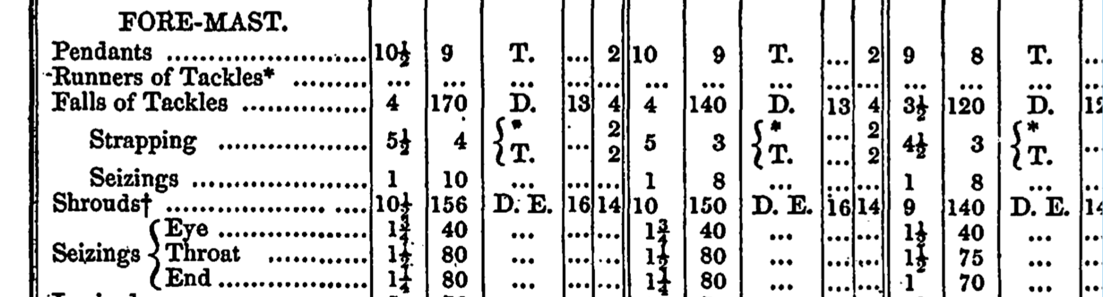

publication includes a comprehensive table listing information about different

sized navy sailing ships of the period including all ropes used for standing

and running rigging. Each rope is named

and listed as hawser laid, as cabled or as tapered and cabled. See the figure below for an example:

Steel’s General View sample

A

transcribed version of Steel’s A General View is available from Y. Miroshnikov.

There

were multiple editions of Steel’s A General View published, but

the transcribed version from Y. Miroshnikov with the

data from 1781 & 1799 is the only one I have found on-line.

In

1794 David Steel had published a multi volume The

Elements of Practice of Rigging and Seamanship. He included an updated version of his rigging tables

in the 2nd volume as well as other information about the rigging of

British navy vessels.

Steel

then created a small book that included the rigging related material in The

Elements that he called “The Art of Rigging” He

included an updated version of the tables of navy ship rigging as an appendix

in the new book whose full title reads:

The Art of Rigging:

Containing an Alphabetical Explanation of the Terms, Directions for the Most Minute

Operations, and the Method of Progressive Rigging with Full and Correct Tables

of the Dimensions and Quantities of Every Part of the Rigging of All Ships and

Vessels

The

first edition of the Art of Rigging was printed in 1796 and is available

as print on demand and in paperback on Amazon

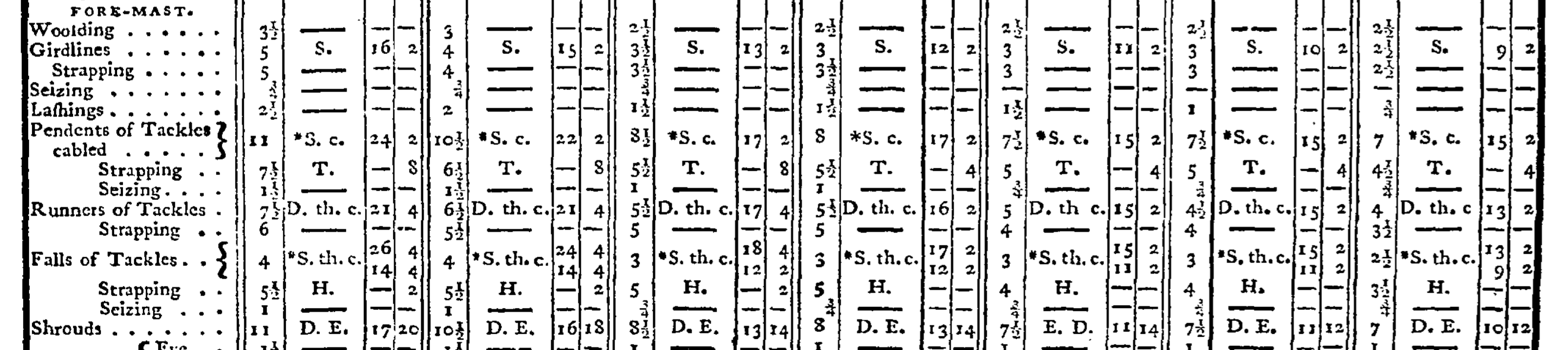

The

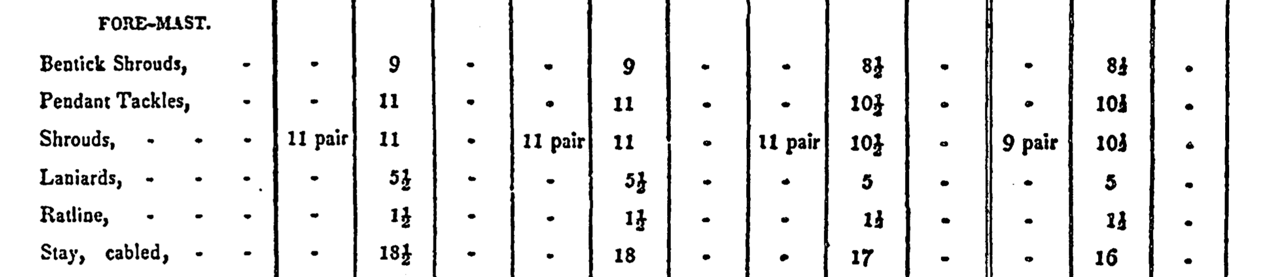

tables in the first edition of the Art of Rigging were simplified

somewhat from the tables in A General View (for example by removing the

notation of which ropes were hawser laid - since all but the ropes that were

cable laid were hawser laid, that made sense), as can be seen in the following

example:

Steel: Art of Rigging First Edition sample

A

second edition was printed in 1806 and is available from the Internet Archive

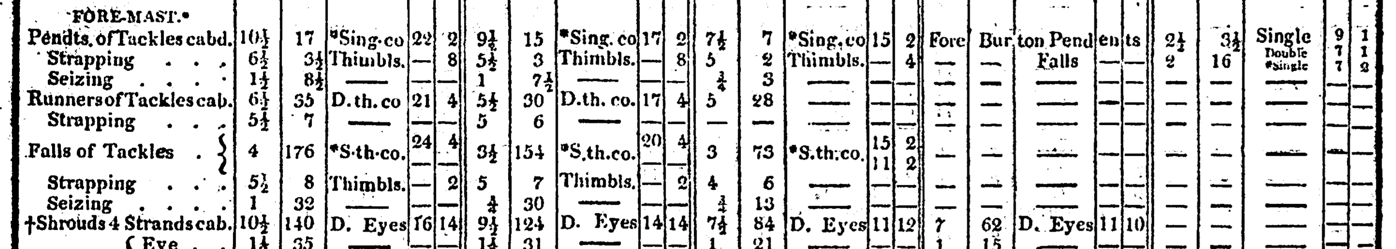

The

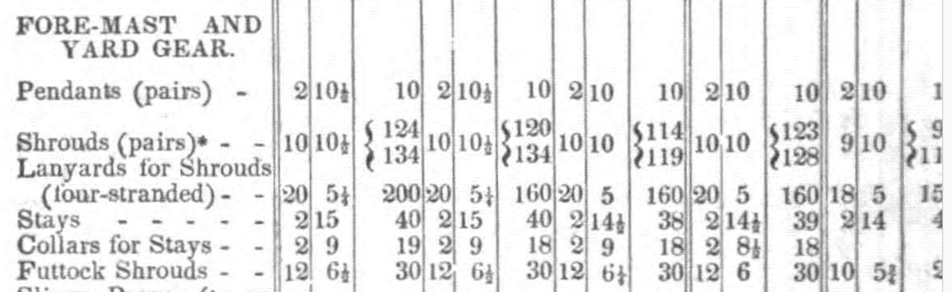

second edition added information about the rigging of merchant ships, and is 13

pages longer than the first edition.

Steel: Art of Rigging Second Edition sample

A

third edition was published in 1818 but I have not found a copy of that

on-line.

The Art

of Rigging was taken over by George Biddlecombe who published a revised

version in 1848. A copy of the 1848

edition is available for free from Google Books,

as is a later version

from 1925, which was also reprinted as a paperback.

The tables in the Biddlecombe version were simplified even

further with the removal of any mention of cabled rope as can be seen in the

following example:

Biddlecombe: Art of Rigging – 1848 sample

American Navy ship

rigging information

Peter Force published a comprehensive set of tables of the

masting and rigging of US Navy vessels in 1826.

He called it:

Tables Showing the

Masts and Spars, Rigging and Stores, etc. of Every Description, Allowed to

Different Classes of Vessels Belonging to the Navy of the United States

I

obtained a copy of the tables and posted it here.

The information in the Force Tables is generally

consistent as to rope sizes for merchant vessels with the information in the

Steel Art of Rigging publications.

See, for example the following example:

Force Tables example

Brady’s The Kedge-Anchor

from 1849 also has a set of tables showing rigging lines for navy vessels and

their sizes. See the following example:

Brady: The Kedge-Anchor – 1849 sample

Underhill information

Harold A. Underhill includes tables of standing rigging

(table 19), running rigging for square sails (table 21), and running rigging

for fore and aft sails (table 22) in his book Masting and Rigging the

Clipper Ship and Ocean Carrier (1946).

Underhill does not say what the source was for his numbers.

Lankford information

Ben Lankford created an excellent set of drawings of the

McKay clipper ship Flying Fish in 1979 for Model Shipways. The drawings include the sizes of all of the

ropes and chains used in both the standing and running rigging. Some of the sizes on the drawings differ from

the sizes shown by contemporary sources

but, overall, in my opinion it is the best single source for information on the

rigging of mid 1800s clipper ships. That

said, the Lankford drawings do not include any mention of the types of rope

used on large sailing vessels.

McLean information

Duncan McLean, writing for the Boston Daily Atlas,

wrote many articles on the launching of many clipper ships, including those

built by Donald McKay. In his story on the Flying Cloud McLean said that

the Flying Cloud was rigged the same as was the Stag Hound. McLean included information about the sizes

of some of the standing rigging in his article on the Stag Hound. The

information he provides is incomplete and a bit confusing but is worth taking a

look at. McLean also said that the

standing rigging for at least the Flying Fish was four-strand and

made of the finest Russian hemp.

Ropemaking information

David

Steel published a two-volume book on the Elements

and Practice of Rigging and Seamanship in 1794. A chapter in the first volume focused on ropemaking.

H.R

Carter published a number of books about ropemaking. I found two in particular to provide helpful

information: Modern Flax, Hemp, and Jute Spinning and Twisting published in 1907 and Rope, Twine and Thread

Making published in 1909.

Information about the

rigging of sailing ships

Of course, all of the books mentioned above include more

than just tables of rigging sizes and are all useful aids to understand the

rigging of sailing ships of all descriptions.

There

are a number of books specifically on the topic of the rigging of large navy

and merchant sailing ships, all of such books I have found provide at least

some useful information.

One particularly detailed book is Lennarth

Petersson’s Rigging Period Ship Models,

published in 2000, which goes line by line through the rigging of an English

frigate built in 1785 based on a contemporary model of the vessel with the

original rigging largely intact.

James Lees-The Masting and Rigging of English Ships of

War 1625-1860, originally published in 1979, also goes line by line through

the rigging of English ships of war and, in addition, contains a lot of

additional information such as how the sizes of deadeyes and their lanyards can

be calculated.

The Ashley Book of Knots, published in 1944, has

quite a bit of useful information beyond how to tie knots, including about

things such as hearts and deadeyes.

What information I used

for deciding on the rigging sizes for my Flying Cloud model

I find that the tables in the second (1806) edition of the Art

of Rigging have the set of information that best matches what I think was

still being used in the mid 1800s on merchant vessels (including U.S. merchant

vessels) – for example, as shown in the sample from the second edition above,

it shows the fore stays as being 10½ inch cabled 4-stranded rope. This matches what Duncan McLean wrote about

some of the McKay clippers, for example this about the Flying Fish “Her heavy standing rigging is of four stranded, patent

rope, made to order of the best Russian hemp, and varies from 10½ to 8 inch.” But this source

does not include all the lines that the Flying Cloud had and there were

some differences between this and other sources.

To determine the final rope sizes, I made spreadsheets that

compared the sizes from the Steel’s A General View, the second edition

of his Art of Rigging, the 1849 version of Biddlecombe’s Art of

Rigging, Force Tables, Underhill Masting and Rigging as well

as the Flying Fish drawings from Lankford. The sizes listed were generally consistent

when normalized for a 1600-ton ship, where the sizes were not consistent, I

picked what seemed to me to be the best size.

I then created spreadsheets of the rigging that used the sizes I had

picked along with sizes that made sense for the lines that were not covered by

any of the sources (the skysail lines for example).

Where the source had information for different sized ships,

I normalized the size values for a ship the size of the Flying Cloud by

comparing the sizes for smaller ships and how the sizes of rope increased based

on the size of the ship. I then applied

that same increase to the largest size ship in the table to get an

approximation of the size that would have been used on a ship the size of the Flying

Cloud.